On the evening of February 28, 2012, a group of men entered a locked and guarded safe at Mozambique’s National Directorate of Land and Forests. From a stockpile of elephant tusks and rhino horns, collected by rangers, police, and the Ministry of Agriculture over eight years, the trespassers began to select their booty: ivory.

They took their time. Unconcerned about being caught by the 24-hour private security firm or the closed-circuit cameras that guarded the building, they selected only the most valuable ivory tusks—leaving behind small and spoiled specimens. By morning, nearly 266 tusks would be gone, representing at least 133 animals, and weighing nearly a ton. The police would investigate, but never question the security guards, nor check the surveillance footage. The ivory would quietly vanish for some Asian shore, where it could fetch as much as 2.2 million dollars. Mozambique’s coveted stockpile of confiscated ivory was no longer. A few thieves and bribes had left the national vault empty.

Mozambique is losing the battle against the illegal wildlife trade before it has even begun to fight.

This is the reality of illegal ivory trade in Mozambique: a poorly managed and corrupt system of failing checks and balances where anyone, from a low-level private security guard to a high-level politician, can be bribed to turn a blind eye. And the problem is growing. In 2010, the last time CITES and Traffic ranked offenders, Mozambique scored among the worst—tying only with Vietnam, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—for failing to prevent ivory smuggling and elephant poaching. In 2012, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) gave the country a flunking red grade, as part of its Wildlife Crime Scorecard initiative, for “failing on key aspects of compliance and enforcement,” emphasis in the original.

Still emerging from a 25-year civil war, Mozambique is a country only now beginning to seriously secure its natural heritage. With twelve National Parks, thirteen Controlled Hunting Areas, and one Forest Reserve, the nation is home to some of the most spectacular forms of African wildlife—including giant pangolins, wild dogs, rhinos, leopards, lions, and elephants. In total, the nation’s elephant population is estimated to be around 18,000 animals, with the majority living in the Niassa National Reserve on the Tanzanian border. But little by little, the nation’s elephant population is being whittled away by poaching. Mozambique is losing the battle against the illegal wildlife trade before it has even begun to fight.

From the Port of Pemba to the Shores of Asia

Pemba is a dusty swamp of a city. Perched on one of the largest deep-water bays in the world, Pemba expanded haphazardly from a small port town out onto a bulbous peninsula of land and beyond. The airport, once on the outskirts of the city, now lies just on the edge, with planes taking off daily over mud-walled homes mixed with industrial installations built by the burgeoning natural gas industry.

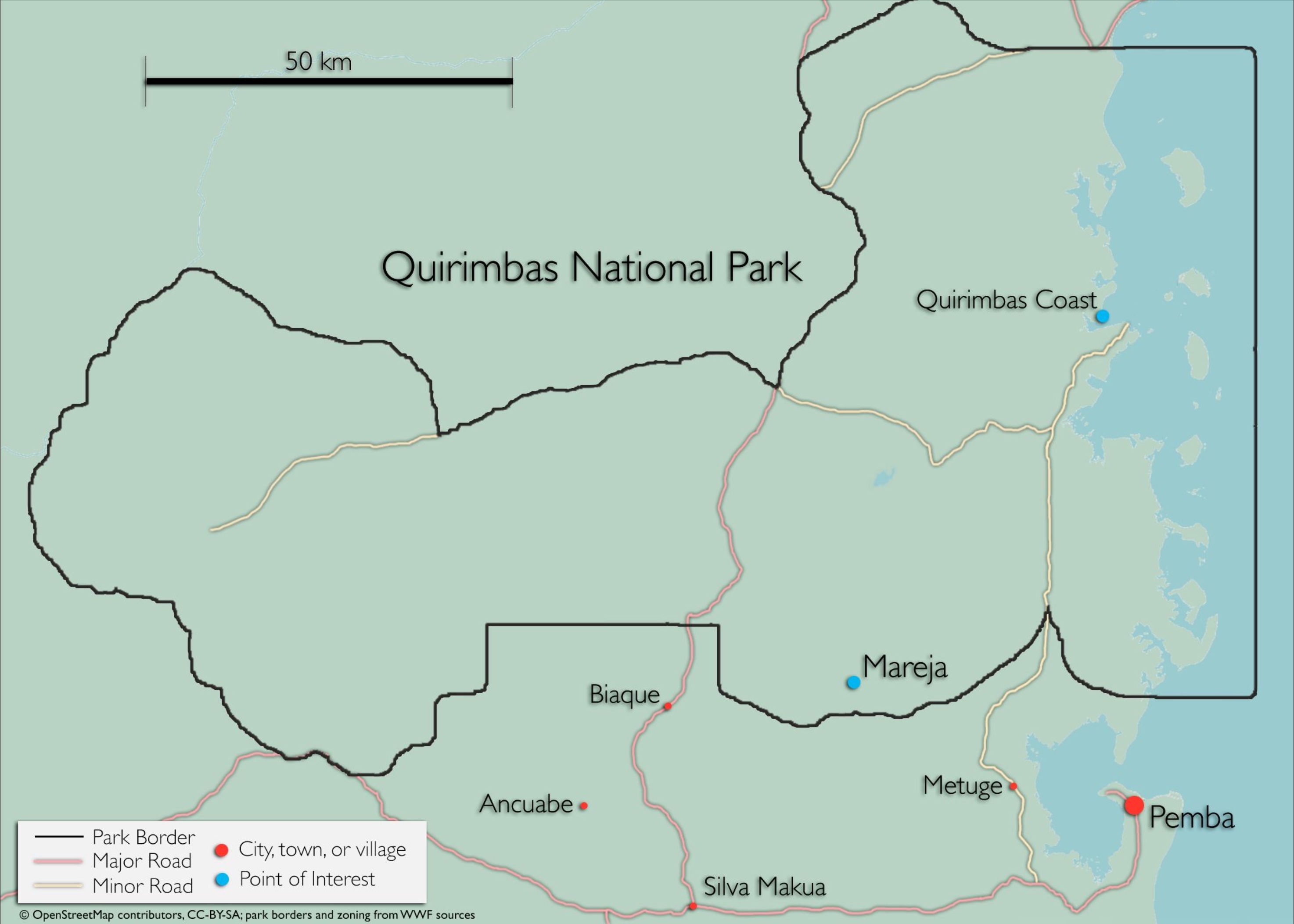

To the north of Pemba bay lies the Quirimbas seashore and its many islands—the real reason for the creation of the Quirimbas National Park. With miles of unspoiled reefs and beaches, the diving is among some of the best in Africa. To the south of the bay, along the peninsula side, miles of beaches head south toward Ilha de Moçambique, with the occasional fishing town being the only testament to human life along the shoreline. And, to the northwest of the bay lies the stretching miombo forests that make up the post-hoc interior of Quirimbas. Though technically a single block, the parklands are really a patchwork of villages, roads, forests, and savannah. Yet from the bay of Pemba, the park looks like one vast unexplored expanse.

It was just off the bay, in a partially restored colonial era building, that I met with Mark Hoekstra technical advisor to the park and a representative of the WWF. Hoekstra, an earnest Dutch conservationist, has over 25 years of experience in sub-Saharan Africa. We talked in a lightly air-condition room in a building that serves as both the park’s headquarters and the base for the WWF’s advisory services. To help protect Quirimbas, the WWF is spearheading a initiative to rezone the park into three total-protection areas, with an emphasis on community management and a balance between nature and sustainable usage. But the drive is being threatened by poaching.

“We had, last year, an incredible increase in elephant poaching, then consequently trade in ivory,” he told me.

A year earlier, in 2011, a helicopter had been spotted poaching elephants in Quirimbas. The poachers, well-armed and organized, were seen and photographed, but the helicopter’s occupants were never identified nor caught.

Officially, only 35 elephants were killed in Quirimbas in 2011. But, unofficially, it is impossible to know how many carcasses are never found and go undocumented. The last publicly released census numbers from the same year put the elephant population at only 555 individuals, but a corridor between Niassa and Quirimbas, means that animals can easily roam north or south as the seasons change. The trade in ivory and illegal timber from Niassa and Quirimbas also follows this migratory route north toward the Tanzanian border. But, more often than not, the timber and ivory from the eastern portion of Quirimbas finds its way to the deep-water port of Pemba—an attractive alternative to land transport.

“Early last year,” Hoekstra recalled, “there was a container amongst many other containers sitting here in a ship in Pemba. It was about to go, I think it is a linha verde, the green line, in Maputo, that got a phone call from someone, saying there’s suspicious cargo on that ship.”

He was speaking of the Kota Mawar, a ship registered to SDV-AMI, and bound for China. In January 2011, six provincial Forestry and Wildlife Services inspectors had allowed 161 containers of illegal timber to be loaded onto the ship. And, among some of the cargo of illegal timber were 126 tusks, elephant organs, and pangolin scales. The containers holding the wildlife contraband all belonged to the Chinese logging company MOFID—which had previously been implicated three times in the illegal export of timber, in 2004, 2007, and 2009—yet continued to be allowed to operate.

Enlarge

“These illegal loggers and others are faced with park staff, police, etcetera, who are prone to bribing; this is an issue.” Hoekstra said. “This is just one case…so how many cases are there that we don’t find?”

The Ministry of Agriculture confiscated the ivory and timber—with the tusks eventually shipped to Maputo as part of the ongoing investigation—and sanctioned the inspectors. It remains unclear, but after being sent to Maputo, the ivory would have most likely been put in the safe at National Directorate of Land and Forests—and subsequently found its way back onto the illegal ivory market in early 2012 when the safe was raided. Outside of sanctions, no legal charges were brought against anyone involved in the smuggling, and the two Chinese nationals implicated in the trafficking ring fled the country in July 2011.

Death in the Dry Season

Sweeping green miombo forests make up much of the interior of Quirimbas, punctuated by towering inselbergs and the occasional open savannah. But during the peak of the dry season, in late August and early September, the green woodlands turn brown and the stands of barren trees in the park become eerily reminiscent of some great northern European forest at the end of autumn—with bare branches overhead and brittle leaves underfoot. The lack of rain concentrates the park’s animals around a few permanent water sources. And, the elephants use the large dry riverbeds as highways in their great search for water and food, making them an easy target for poachers.

“That’s where they shot her,” Ali Bacar told me in village Portuguese. He was pointing to the gaping wound where the poachers had removed a hunk of flesh from the young dead elephant. Bacar is the head ranger for the Mareja Reserve, a public-private partnership that manages some 39,000 hectares in Quirimbas. Originally founded by Dominik Beissel, a German national, the reserve aims to protect the forest with an augmented force of paid community rangers, who are often outgunned and outnumbered in the increasingly lethal war on poaching.

Left: Ali Bacar is the head ranger at Mareja. He’s been a ranger for over 12 years at the reserve, and had formal training with the national park service at Gorongosa Park in the center of the country. Right: Six years before the official creation of the park, Dominik Beissel created the Mareja Reserve, a ecotourism partnership that helps protect some 39,000 hectares of miombo forest guarded by community rangers.

The rangers had taken me to the site of the kill on the afternoon of September 7, 2012. The female elephant was lying on her side in the dark forest, near a riverbed. Unlike much of the surrounding woodland, the trees around her body were still green, drawing their water from some deep underground source.

“There was another elephant here, too,” Bacar said, and he gestured with his hand indicating it was smaller, perhaps a sibling or a child of the dead animal, who had come to investigate the death. Unlike so many other poached elephants in the forest, her head was untouched, and her large grey eyelids closed. Most likely, the poachers spotted her body in the thick miombo woodland and shot her before they realized she was tusk-less and would return no reward. But before they left her to rot, they’d cut out a chunk of her shoulder for a quick meal or perhaps to recover their spent bullets. The freshness of the kill made the animal seem almost alive, save for the wound.

The attack had come the day before. Early in the morning, the community rangers were awoken to the rat-a-tat-tat of a Kalashnikov rifle. I was in the reserve during the attack and Bacar came to my door at 6:30 that morning.

“We’ve had four shots fired southeast from here,” he told me. About an hour later we heard another shot, this time with more bass and more force. It was the kill shot, in this case to the heart of the already injured animal, and probably made with a more forceful hunting rifle.

Community rangering is complex endeavor. With only minimal training and three old .375 bolt-action rifles, procured by Beissel, the rangers often have to sit on their hands while they wait for park reinforcements to tackle more serious poachers, like the group with the AK-47s that had fired on the elephant that morning. Bacar himself was trained by the national park service in Gorongosa Park in the center of the country, but training is no substitute for the weaponry necessary to fight poachers.

It wasn’t until midday that the park sent out two formal rangers, one armed with an AK and another with a bolt-action rifle, to join the group of community rangers. The two rangers, Thomas and Fonseca, were dressed in street clothes, in contrast to the uniformed community rangers. Their superior officer had instructed them to assist the community rangers, but not to engage armed poachers directly without even more reinforcements.

“What a total nightmare,” Beissel said as he described the attack. “Total anarchy and the park standing by to watch the carefully guarded resources destroyed…leaving behind a wasteland that will have made one or two people rich.”

Beissel, a tall lanky conservationist, has been watching over the reserve’s elephants for more than 16 years. Frustrated by a lack of response from park officials, Beissel has more than once put himself in direct danger as he tracks and monitors poaching threats with his team of eight rangers. It was Beissel that had photographed the helicopter of poachers a year earlier in the park.

“If there is [sic] to be any elephants at all, we need some enforcement success,” Beissel told me via email. In early September 2012, he was home in Europe caring for his newborn son when the attack occurred.

Back in the forest that afternoon, there was an eerie sense of stillness surrounding the scene. The rangers seemed uncomfortable as I hiked out and left them to make camp near the dead elephant. The next day, they told me that the poachers had double backed. We had been watched. Something, it seemed, they knew on a subconscious level that afternoon, but had never communicated to me at the time.

Enlarge

Even with eight community rangers and two park guards camping in the forest that night, the attack wasn’t over. A little over a kilometer from the dead female, a male was killed only two hours after I left the rangers. This time the rangers were able to get close enough to observe the poachers, but with direct instructions from the national park service not to engage, the rangers were left helpless to watch as the poachers hacked off the elephant’s face to recover its ivory.

Two weeks later, the guards took me to the bodies of two other elephants killed in the same weekend raid. In total, Beissel estimates that 13 animals were killed in the reserve that September.

During the four-day attack Bacar was in constant contact with the national park service, but the chief warden continuously instructed the rangers not to engage the poachers, and promised to send more guards as soon as possible. The help came too late, however, with an elite force of police and rangers arriving nearly eight days after the initial shots were fired—far too long a turnaround time when poachers can enter, track, kill, and exit all in a single day.

Logger's Roads and Container Ships

“Certainly, the timber industry and the wildlife trade are naturally linked throughout Africa,” Julian Newman, the Campaign’s Manger for Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), told me via telephone, “The timber companies provide easy access to areas via roads and infrastructure and also a ready-made means of transport to the Asian markets with the containerization of timber.”

Newman was just back from an investigation in northern Mozambique, where he and his team concluded that in 2012 between 189,615 and 215,654 cubic meters of timber was illegally imported to China from Mozambique. They also found that companies like MOFID, caught smuggling ivory in 2011, had deep ties to the political elite within the ruling party of FRELIMO guaranteeing their access to illegal timber for years to come. And, while much of the illegal wood harvested by MOFID and others comes from outside the park, Quirimbas is not immune to the logging boom engulfing the region.

Nearly a month to the day after the poaching incident, Bacar and his rangers took me to investigate an illegal logging road at the edge of the Mareja Reserve inside the park. The road was cut into the dry forest after a fire had been set to sweep the land of underbrush. Along the main logging road and a smaller access route, the rangers counted and marked over 50 downed trees ready to be transported out of Quirimbas. The rangers also found an elephant carcass, whose tusks had already been removed. Bacar explained that the logs would be sent through the town of Metuge and make their way to the port in Pemba, after being processed near the city.

Enlarge

In contrast to the remoteness of the region, as we stood in the forest amongst downed trees in the late afternoon sunlight, Bacar pulled out his cell phone to call the park warden and discuss the situation. It was agreed that the ranger station in Metuge would be put on high alert for loggers’ trucks and would stop anything coming out of the district. But, when I asked Bacar few days later what had happened to the timber, he just shrugged his shoulders, “I was told that the ranger in charge of the station had a headache and had not shown up for work the day the logs were transported.”

With the logger’s roads, however, had come the elephant poachers. Ivory can’t be moved without a means of transport—both from the forests to the ports, and from the ports to the international markets of Asia. Together the legal and illegal timber industries of Mozambique provide a vast ready-made shipping network, with boats leaving for Asia weekly. But, proving the links between the ivory industry and the timber companies is difficult.

“In 2011, we had a tip-off that ivory was being trafficked from Nacala port to a port in Southern China in containers of prohibited roundwoods,” Newman of EIA explained, “But while the informant provided evidence of the timber smuggling, they could not do so for the ivory.”

Without scanners at ports, timber must be physically lifted and moved in order to prove that ivory is not being concealed somewhere within the transport container. And even then, shrewd smugglers can find clever ways to conceal their wildlife goods.

“In July 2009, Vietnam customs at the port of Hai Phong stopped a shipment of sawn wood which had originated in the port of Mochimboa da Praia in Cabo Delgado,” Newman told me, “Upon inspection, the large bundles of sawn planks were found to conceal 600 kg of ivory tusks.”

The planks had been pre-cut to create secret cavities where the wildlife contraband could be stored, like a hiding place cut into the pages of book. The logging company, the Chinese-owned Pemba-based Senlian, had shipped the timber out of the Mochimboa port, which lies just north of the Quirimbas National Park. Despite this breach of international law, Senlian is still active in the region, shipping timber out of the ports of Pemba and Mochimboa da Praia.

An Uncertain Future

The dry season of late September finally gave way to the rains, and the forest once again became a dense, lush, hiding place for the elephants of Quirmbas, but though the poaching slowed, it did not stop. Each dry season threatens to see the forest raided once again for its last remaining elephants. The illegal logging never ends, however, and aerial surveys have revealed that timber operations and now illegal miners all are within the park boarders.

Speaking of the miners, Hoekstra from the WWF told me that they had already had some law enforcement success. “We’ve already seized equipment, already groups of foreigners working with nationals illegally in the park have been stopped,” he said. But, of the mining boom itself, he added “I have a feeling we’re only at the start of all that.”

And when Beissel returned to the Mareja Reserve in late November, he noted that there were some signs the tide could change. “We have been working with members of the presidential guard who are well educated and armed…” he told me via email after his return.

But still, he lamented on the lack of law enforcement success. “On my first op, I managed to come up behind the poachers as I walked in from the coast. They were warned off by a bamboo cutter and disappeared,” he said, “Later we heard that they were stopped by police in Metuge in possession of four firearms and army uniforms. Unfortunately, they were let go.” But he added, “The main culprit, however, has been caught with 437 rounds of ammo in Napuda and is currently in Pemba.”⌷

Update

In mid-2014 the WWF released the results of their 2013 survey of Quirimbas National Park. According to the Fund, nearly 50% of all elephants spotted by the survey team were carcasses. The team also estimated that the park lost between 480 and 900 elephants between 2011 and 2013. Colman O’Criodain, WWF International’s Policy Expert on Wildlife Trade, said “Mozambique has emerged as one of the main places of the slaughter of elephants and ivory transit in Africa and as a profitable warehouse for transit and export of rhino horn for the Asian markets. We need to see urgent action and ongoing commitment to combat these illegal activities.”

This piece is part of a larger iPad project. To download the entire iBook visit the iTunes store. Special thanks to Janelle Leung and Cherry Republic for their support. Story, photos, and video by Cody Pope.

I love what you’ve done here, with the Aesop story engine … and yes, am really interested in known more about this project and will check out your book, on iTunes. Thanks!

Btw, did you create this theme yourself, or is it available commercially? Again, my sincere thanks.

Thanks! I’m using the Novella theme from Nick H and his team at Aesop.

Read all about this tragic on wildlife & forest reserve happening in Mozambique a sad part. Government of Mozambique should take some concrete steps to preserve this wild life & nature.

[…] https://countingthedead.com/2014/08/23/counting-the-dead/ […]

Thank you for shedding light on the shamefull theft that’s going on unchecked in this beautiful country. It’s criminla that little is being done to stop it going on. Governments should protect the heritage of their people. Such a sad loss of wildlife and trees. Hopefully action will be taken before these beautiful, natural treasures are lost.

MY HEART BREAKS

PLEASE TELL US HOW TO HELP

A country with such incredibly potential and so many challenges. I truly hope that Mozambique’s biodiversity is not lost before the general population has a chance to appreciate it. Scientists are still discovering treasures this country holds. It can be so very disheartening when faced with the fact that so much will disappear. ever the optimist, I believe while there is still life, there is hope. And we must do what we can to help Mozambique hang on to it’s natural heritage.

[…] https://countingthedead.com/2014/08/23/counting-the-dead/ […]

This reads just like the North Luangwa Park in Zambia in the late 1980’s. Everyone’s fingers are sticky with blood and greed, and so the few dedicated guys on the ground are fighting against all odds and with their lives. It is such a disgrace. And it seems at the moment as if the ‘rest of us’ are not enough to halt it. Surely we can do better than this??!!

[…] Counting the dead (AESOP) […]